the man who fell out of bed

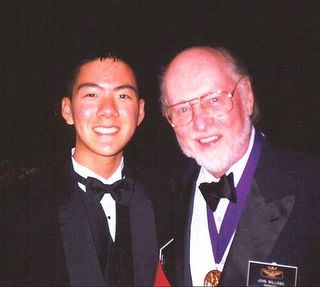

i met oliver sacks in high school, at the now infamous "arizona thing." towards the end of senior year, i was invited--along with 400 or so other high school students--to an all expenses-paid 4-day vacation at the phoenician resort. there, we students had the opportunity to cavort with america's rich and famous. lauryn hill, gen. wesley clark, arthur golden, ben carson, 23 nobel prize winners... it was surreal, to say the least. below is a photo of me and composer john williams. nice guy, although not as tall as i'd thought.

me with the man

anyway, oliver sacks was there too, and at the time i had no clue who he was. i didn't know yet that i wanted to be a physician, and dr. sacks struck me as more odd than inspiring. he mumbled and stuttered throughout his speech, his eyes fixed on his feet, and he wrote books with strange titles like the man who mistook his wife for a hat. what a freak.

but, five years later, almost to the day, i've picked up his book and found it to be absolutely mesmerizing. i still only have a rudimentary grasp of the biology with which he's concerned--i know the left and right brain stereotypes like anyone else, and i know how strokes and brain tumors come about. but it's enough for me to appreciate some of the stories he tells. his patients are extraordinary--a man who, yes, mistakes his wife for a hat, a woman who has no sense of "left" (think derek zoolander's ambi-turning deficiency, but without the humor), and a man with memento-style amnesia. human consciousness is one of those black boxes that never really piqued my interest--i'm perfectly happy not knowing how it works, so instead my professional interests, i assumed, would concern diseases with less metaphysical weight. still, dr. sacks' book makes me wonder...

here is an excerpt:

Thus, in one patient under my care, a sudden thrombosis (clot) in the posterior circulation of the brain caused the immediate death of the visual parts of the brain. Forthwith this patient became completely blind--but did not know it. He looked blind--but he made no complaints. Questioning and testing showed, beyond doubt, that not only was he centrally or 'cortically' blind, but he had lost all visual images and memories, lost them totally--yet had no sense of any loss. Indeed, he had lost the very idea of seeing--and was not only unable to describe anything visually, but bewildered when I used words such as 'seeing' and 'light.'... His entire lifetime of seeing, of visuality, had, in effect, been stolen.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home